Imagine a giant, unstable atomic nucleus, bulging with energy, ready to tear itself apart. This isn't science fiction; it's the profound reality at the heart of Fundamentals of Nuclear Fission, a process that reshapes matter and releases incredible power. For decades, humanity has grappled with both the destructive potential and the immense benefits of coaxing these atomic giants to split, unlocking secrets that power cities and define modern physics.

At a Glance: Understanding Nuclear Fission

- What it is: The splitting of a heavy atomic nucleus into two or more lighter nuclei, releasing massive amounts of energy, neutrons, and gamma radiation.

- Why it happens: Heavy nuclei are inherently less stable than medium-sized nuclei. Splitting allows them to achieve a more stable configuration.

- How it starts: Can be induced (e.g., by absorbing a neutron) or occur spontaneously.

- Key products: Highly energetic fission fragments, prompt neutrons (crucial for chain reactions), and gamma rays.

- Energy release: A single fission event unleashes about 200 million electron volts (MeV) of energy – vastly more than any chemical reaction.

- Applications: Powers nuclear reactors, provides medical isotopes, and, infamously, fuels atomic weapons.

The Unstable Giant: Why Atoms Split in the First Place

To truly grasp nuclear fission, we must first understand the fundamental nature of atomic nuclei. Picture the nucleus not just as a static blob of protons and neutrons (collectively called nucleons), but as a dynamic entity striving for stability.

Here's the key: the actual mass of a nucleus is always slightly less than the sum of the individual masses of its free protons and neutrons. This missing mass, known as the "mass defect," isn't lost; it's been converted into the "binding energy" that holds the nucleus together, according to Einstein's famous equation, E=mc². The greater the binding energy per nucleon, the more stable the nucleus.

Nuclear stability isn't uniform across the periodic table. It peaks around mass number 56, which corresponds to elements like iron. This means iron-56 is one of the most stable nuclei in the universe. Nuclei much lighter than iron tend to gain stability by fusing (combining), while those much heavier — like uranium or plutonium — find greater stability by splitting apart. Fission is nature's way for these atomic behemoths to shed mass and move towards that energetically favorable sweet spot.

Imagining the Atomic Split: The Liquid Drop Model

How does a nucleus actually go about splitting? For decades, scientists have used an elegant analogy called the "liquid drop model" to explain this complex phenomenon. Imagine a nucleus not as a rigid structure, but as a tiny droplet of an incompressible, electrically charged liquid.

In this model, two opposing forces are at play:

- Strong Nuclear Force: This is like the surface tension of a liquid drop. It's a powerful, short-range attractive force that pulls nucleons together, favoring a compact, spherical shape.

- Coulomb Repulsion: The protons within the nucleus are all positively charged, and like charges repel each other. This is a long-range repulsive force that constantly tries to push the nucleus apart.

Under normal conditions, the strong nuclear force keeps the nucleus intact. However, if the nucleus absorbs enough excitation energy — perhaps from an incoming neutron — it begins to deform, stretching out like a vibrating blob of jelly. As it elongates, two things happen: the surface area increases, making the strong nuclear force (surface tension) less effective at holding it together, while the repulsive Coulomb forces between the protons, now further apart, actually decrease but become more effective at driving the split.

Eventually, the nucleus reaches a critical point known as the "saddle point" (think of a mountain pass). This is the height of the "fission barrier." If the nucleus has enough energy to overcome this barrier, the Coulomb repulsion takes over, driving further elongation. The "scission point" is then reached, where the neck connecting the two halves finally breaks, and the nucleus bursts into two (or sometimes three) smaller, highly charged fragments.

Triggering the Divide: Induced vs. Spontaneous Fission

Not all nuclei split in the same way, nor do they all require the same push. There are two primary types of nuclear fission:

Induced Fission: The Atomic Spark

Induced fission occurs when a nucleus is excited by an external stimulus, gaining enough energy to overcome its fission barrier. Think of it as deliberately breaking a stick.

- Particle-induced Fission: The most common and industrially important form of induced fission involves the capture of a neutron. When a neutron strikes a heavy nucleus and is absorbed, it adds its binding energy and kinetic energy to the target nucleus, causing it to become highly unstable and split.

- Fissile Nuclides: These are the superstars of nuclear technology. Examples include Uranium-233 (²³³U), Uranium-235 (²³⁵U), and Plutonium-239 (²³⁹Pu). What makes them special? They have an odd number of neutrons. When they absorb even a slow, low-energy "thermal" neutron, the binding energy released by the captured neutron is alone sufficient to excite the nucleus beyond its fission barrier. This makes them ideal for controlled chain reactions in reactors.

- Fissionable Nuclides: These nuclei, such as Thorium-232 (²³²Th) and Uranium-238 (²³⁸U), have an even number of neutrons. While they can fission, they require a higher-energy "fast" neutron (typically around 1 MeV or more) to provide the extra kick needed to overcome the fission barrier. The binding energy from a slow neutron isn't enough for them. They cannot sustain a chain reaction with thermal neutrons alone.

- Photofission: While less common for practical applications, fission can also be induced by high-energy gamma rays. This is known as photofission.

Spontaneous Fission: Nature's Own Decay

Some of the very heaviest nuclei don't need an external nudge to split; they do it all on their own. This is called spontaneous fission, a type of radioactive decay.

In spontaneous fission, a nucleus in its ground state (without any added energy) can quantum mechanically "tunnel" through its fission barrier. Imagine a ball at the bottom of a hill magically appearing on the other side without rolling over the top. This quantum tunneling effect is improbable but possible, especially for extremely heavy elements. The probability of spontaneous fission increases dramatically with increasing mass number, becoming the dominant decay mode for some super-heavy nuclides, leading to half-lives measured in fractions of a second.

This natural phenomenon was discovered in 1940 by Georgi Flyorov, Konstantin Petrzhak, and Igor Kurchatov, further solidifying our understanding of nuclear decay processes.

The Anatomy of a Split: What Happens When a Nucleus Fissions

Once a heavy nucleus is sufficiently excited and overcomes its fission barrier, a remarkable sequence of events unfolds:

- Deformation and Oscillation: The nucleus stretches and vibrates, moving past the saddle point.

- Scission: At the scission point, the nucleus literally tears itself into two (most commonly) or sometimes three smaller nuclei, known as fission fragments. The most common split, called binary fission, typically produces fragments with an unequal mass ratio, often around 3:2. For example, uranium often splits into one fragment around mass 95-100 and another around 130-140. As excitation energy increases, this distribution can become more symmetric.

- Fragment Recoil and Excitation: These freshly born fission fragments are highly charged and immediately repel each other with immense force (Coulomb repulsion), recoiling away at high speeds. As they move, they strip off atomic electrons from their surroundings, leaving a trail of ionization. Inside, they are highly excited, often still deformed from the violent split.

- Prompt Emissions: To shed this excess energy and adjust their shape, the fragments rapidly emit:

- Prompt Neutrons: These are released within an incredibly short timeframe, roughly 10⁻¹⁸ to 10⁻¹⁵ seconds after fission. An average of about 2.5 neutrons are emitted per fission event in common fuels like uranium-235. These "prompt" neutrons are crucial for sustaining a chain reaction.

- Prompt Gamma Rays: High-energy photons are also emitted almost instantaneously (within about 10⁻¹¹ seconds) as the fragments stabilize their internal energy states.

- Radioactive Decay of Fission Products: After shedding prompt neutrons and gamma rays, the fission fragments slow down, pick up electrons to become neutral atoms (now called fission products), and find themselves highly unstable due to an excess of neutrons. They then embark on a series of radioactive beta decays, emitting electrons, antineutrinos, and often more gamma/X-rays, over timescales ranging from fractions of a second to many years. A tiny fraction of these beta decays also lead to the emission of "delayed neutrons," which, despite their small number, are vitally important for controlling nuclear reactors.

The Staggering Energy Release

A single typical fission event, such as that of uranium-235, unleashes approximately 200 MeV (million electron volts) of energy. To put this in perspective, burning a molecule of coal releases only a few electron volts. This 200 MeV is distributed as follows:

- ~169 MeV: Kinetic energy of the recoiling daughter nuclei (fission fragments). This is the energy that ultimately translates into heat in a reactor.

- ~4.8 MeV: Kinetic energy of the prompt neutrons (typically about 2.5 neutrons, each with ~2 MeV).

- ~7 MeV: Energy carried by prompt gamma ray photons.

- The remaining energy (around 19 MeV) is released later through the radioactive decay of the fission products, primarily as beta particles, antineutrinos, and delayed gamma/X-rays.

This incredible energy density is what makes nuclear fission so compelling for power generation and so devastating in weapons.

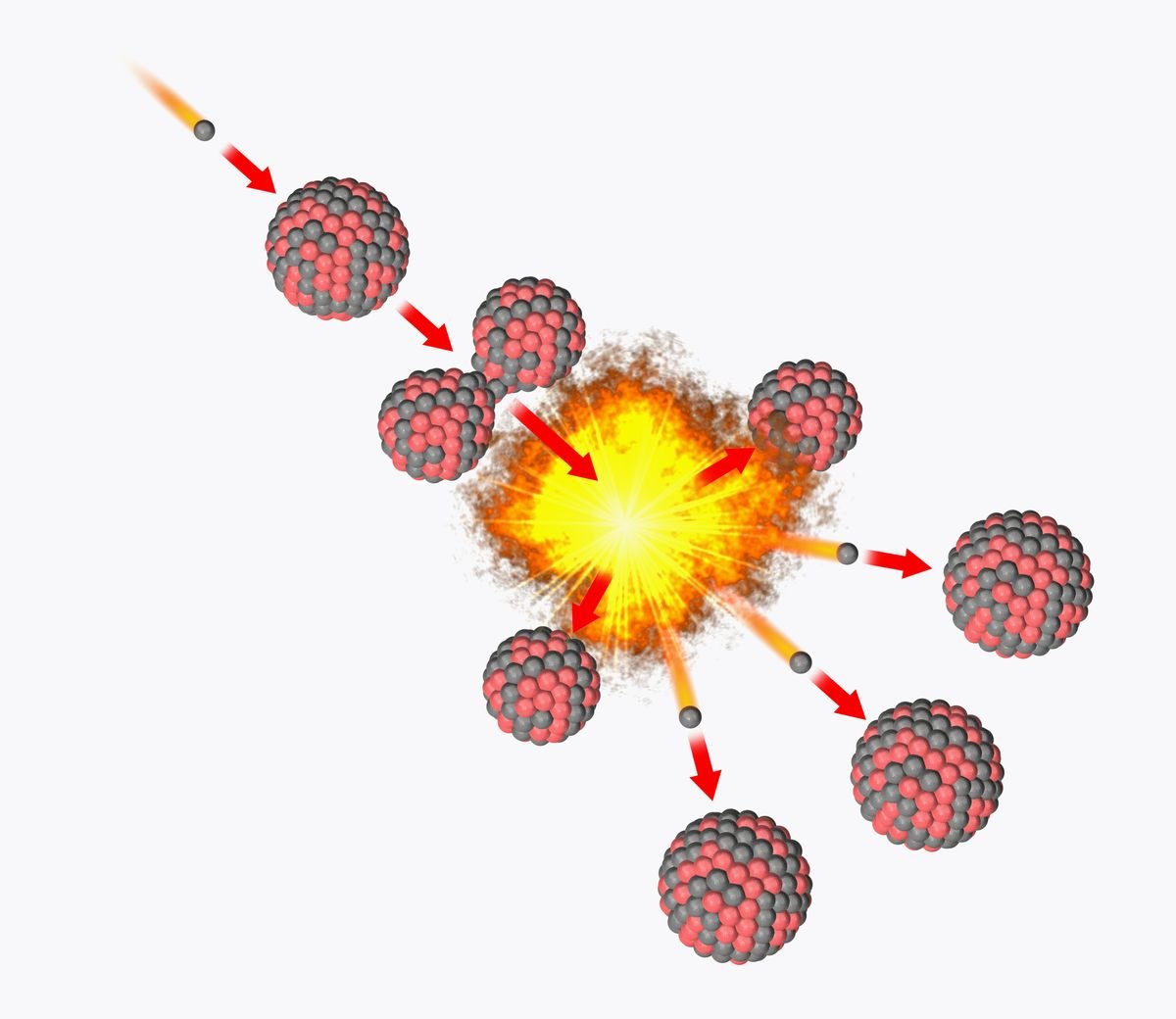

The Power Multiplier: Understanding Chain Reactions

The true game-changer in understanding nuclear fission is the concept of the chain reaction. When a fissile nucleus splits, it releases not only energy but also several new neutrons. These new neutrons, if they strike other fissile nuclei, can induce those nuclei to fission, releasing even more neutrons, and so on. This self-sustaining sequence is a chain reaction.

The behavior of a chain reaction is governed by the neutron multiplication factor (k), which is the ratio of neutrons in one "generation" of fission to the number of neutrons in the preceding generation.

- k < 1 (Subcritical): If fewer than one neutron from each fission event goes on to cause another fission, the reaction dies out. This is a subcritical state.

- k > 1 (Supercritical): If more than one neutron from each fission event causes further fissions, the reaction rate increases exponentially. This is a supercritical state, characteristic of an atomic bomb or the start-up phase of a reactor.

- k = 1 (Critical): If, on average, exactly one neutron from each fission event causes another fission, the reaction proceeds at a steady, constant rate. This is the critical state, precisely what's maintained in a nuclear power reactor.

To control these chain reactions, engineers employ several critical components: - Moderators: The prompt neutrons released during fission are "fast" (high-energy). However, fissile materials like uranium-235 are much more likely to absorb "slow" (thermal) neutrons and fission. Moderators, such as light water, heavy water, or graphite, are materials that slow down these fast neutrons through elastic collisions without absorbing too many of them. This increases the probability of capture and subsequent fission, making a chain reaction possible with common fuels.

- Nuclear Fuels: These are the materials specifically designed to sustain a fission chain reaction. The most common are enriched uranium (containing a higher percentage of ²³⁵U than natural uranium) and plutonium-239 (²³⁹Pu). Another potential fuel is ²³³U, which can be bred from thorium.

Understanding the neutron multiplication factor and the role of moderators is fundamental to designing and operating nuclear reactors, allowing us to harness fission for controlled energy production. Learning how nuclear power generators work truly demystifies this process.

Fission's Footprint: From Power Plants to Weapons

The principles of nuclear fission have found profound and varied applications, fundamentally reshaping our world.

Nuclear Power: Controllable Energy

The most widespread beneficial application of nuclear fission is the generation of electricity. In a nuclear power plant, a controlled chain reaction is maintained at a critical state (k=1) within a reactor core. The immense heat generated by fission is transferred to a coolant (often water), which then typically produces steam. This steam drives turbines, which in turn generate electricity.

As of 2019, nuclear power plants globally provided a significant portion of the world's electricity, with 448 operational reactors contributing 398 GWE (gigawatts electric). Nuclear power offers a low-carbon energy source, though it comes with challenges related to safety and waste management.

Nuclear Weapons: Uncontrolled Force

On the more destructive side, nuclear fission is the principle behind atomic bombs. These devices are designed to rapidly achieve a highly supercritical state (k >> 1), allowing the chain reaction to diverge uncontrollably in a fraction of a second, releasing an explosive force equivalent to thousands or millions of tons of TNT. The sheer scale of energy release in these weapons profoundly changed global geopolitics after their development.

Beyond Power and Weapons: Other Applications

- Research Reactors: These specialized reactors don't typically generate electricity but are crucial for scientific research. They produce intense beams of neutrons used to study materials, as well as radioactive isotopes vital for medical diagnostics and treatments (e.g., in cancer therapy).

- Breeder Reactors: A fascinating concept, breeder reactors are designed to produce more fissile material than they consume. For instance, they can convert abundant uranium-238 into plutonium-239, or thorium-232 into uranium-233, effectively extending the world's nuclear fuel supply.

- Nuclear Waste Management: The radioactive fission products left after a nuclear fuel cycle are highly radioactive and require careful, long-term storage. Nuclear reprocessing aims to recover usable uranium and plutonium from spent fuel, reducing the volume and radioactivity of the remaining waste, moving towards a "closed fuel cycle" that minimizes environmental impact.

A Brief History of the Atomic Age: Key Milestones in Fission

The journey to understanding nuclear fission is a testament to human curiosity and persistence, unfolding over decades with contributions from brilliant minds across the globe.

- 1896: The Dawn of Radioactivity: Henri Becquerel's accidental discovery of radioactivity, observing uranium salts spontaneously emitting rays, laid the groundwork for all future nuclear science.

- 1919: Artificial Transmutation: Ernest Rutherford achieved the first artificial transmutation, changing nitrogen atoms into oxygen atoms by bombarding them with alpha particles. This was the first time humans intentionally altered an element.

- 1932: The Neutron's Unveiling: James Chadwick discovered the neutron, the chargeless particle that would later prove pivotal in inducing fission. In the same year, Ernest Walton and John Cockcroft achieved the first fully artificial nuclear reaction using a particle accelerator.

- 1934: Fermi's Early Experiments & Noddack's Vision: Enrico Fermi, in Rome, bombarded uranium with neutrons, producing a bewildering array of new radioactive elements. German chemist Ida Noddack, reviewing his work, astutely suggested that the uranium nucleus might actually be breaking into "large fragments," a radical idea at the time, largely dismissed by her contemporaries.

- December 1938: The Chemical Proof: In Berlin, chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, replicating Fermi's experiments, chemically identified barium (an element much lighter than uranium) in their neutron-bombarded uranium samples. This was the irrefutable chemical evidence of a nucleus splitting.

- January 1939: The Theoretical Explanation & "Fission" is Coined: Otto Hahn relayed his perplexing results to Lise Meitner, a Jewish physicist who had fled Nazi Germany. With her nephew, Otto Robert Frisch, Meitner theorized that the uranium nucleus had indeed "fissioned" – a term Frisch coined, borrowing from the biological term for cell division. They published their groundbreaking theoretical explanation in Nature.

- February 1939: The Chain Reaction Foresight: Hahn and Strassmann, building on their discovery, predicted the liberation of additional neutrons during fission, hinting at the possibility of a self-sustaining chain reaction.

- April 1939: Neutrons Confirmed, Szilárd's Realization: Frédéric Joliot-Curie's team in France confirmed that fission indeed emitted additional neutrons. Simultaneously, Hungarian physicist Leo Szilárd, who had conceived of the chain reaction years earlier, immediately recognized the implications for a powerful, neutron-driven explosive.

- August 1939: Einstein's Letter: Alarmed by the potential for Nazi Germany to develop atomic weapons, Szilárd, along with fellow physicists Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, drafted a letter for Albert Einstein to sign, alerting President Franklin Roosevelt to the possibility of atomic bombs and the need for American research.

- 1940: Spontaneous Fission & Critical Mass: The discovery of spontaneous fission (by Flyorov, Petrzhak, and Kurchatov) provided another piece of the puzzle. Separately, Frisch and Rudolf Peierls in the UK calculated the critical mass of uranium-235 needed for an explosive chain reaction, showing it was far smaller than previously thought.

- March 1941: Plutonium's Role: Emilio Segré and Glenn Seaborg at the University of California, Berkeley, reported that plutonium-239, a newly synthesized element, was also fissile with slow neutrons. This discovery offered an alternative path to an atomic bomb, circumventing the difficult challenge of uranium enrichment.

- December 2, 1942: The First Self-Sustaining Chain Reaction: Under the stands of Stagg Field at the University of Chicago, Enrico Fermi's team achieved the world's first sustained nuclear chain reaction in Chicago Pile-1 (CP-1), a carefully constructed stack of graphite and uranium. They deliberately brought the reactor to a critical state (k=1.0006), marking a monumental milestone.

- 1942-1945: The Manhattan Project: Driven by wartime urgency, the top-secret Manhattan Project, led by General Leslie R. Groves and scientific director J. Robert Oppenheimer, embarked on the massive undertaking to develop atomic weapons in the United States.

- July 1945: Trinity Test: "The Gadget," the world's first atomic device (a plutonium implosion bomb), was detonated in the New Mexico desert in the "Trinity" test, ushering in the atomic age.

- August 1945: Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The U.S. deployed atomic bombs against Japan: "Little Boy" (a uranium-235 gun-type weapon) on Hiroshima and "Fat Man" (a plutonium implosion weapon) on Nagasaki, bringing a swift and devastating end to World War II.

- 1972: Nature's Own Reactors: French physicist Francis Perrin discovered evidence of natural nuclear fission reactors at Oklo, Gabon. About two billion years ago, when the concentration of fissile uranium-235 was higher (around 3%, similar to today's enriched reactor fuel), geological conditions allowed for a self-sustaining chain reaction to occur naturally for hundreds of thousands of years. This incredible discovery confirmed a theoretical prediction made by Paul Kuroda in 1956.

Harnessing the Atom's Secret: The Enduring Legacy of Fission

The fundamentals of nuclear fission are a profound blend of quantum mechanics, material science, and engineering ingenuity. From the subtle forces within the nucleus to the dramatic energy release that powers reactors or fuels weapons, understanding how heavy atoms divide has been one of humanity's most transformative scientific endeavors.

As we continue to navigate the energy demands of a growing world and the challenges of climate change, the principles of nuclear fission remain critically relevant. Advances in reactor design, fuel cycles, and waste management are continuously being explored, pushing the boundaries of what's possible with this powerful atomic process. The story of fission is far from over; it continues to unfold, promising both grand challenges and immense opportunities for our future.