Imagine a single grain of sand holding the power to light a city. That’s essentially what we ask of uranium when we harness it for nuclear power. But getting that energy out isn't as simple as flipping a switch. It involves a meticulously engineered journey for the nuclear fuel, a complex series of steps known as The Nuclear Fuel Cycle. This cycle is the backbone of nuclear energy, defining how we acquire, prepare, use, and ultimately manage the extraordinary power locked within the atom.

From the moment uranium is unearthed to the final secure storage of its spent remains, the nuclear fuel cycle is a testament to human ingenuity and our ongoing quest for reliable, low-carbon energy. It's a journey filled with specialized chemistry, physics, and engineering, all designed to ensure safety, efficiency, and environmental responsibility.

At a Glance: Understanding the Nuclear Fuel Cycle

Before we dive deep, here’s a quick overview of what makes the nuclear fuel cycle tick:

- It's a Start-to-Finish Process: The cycle covers everything from mining uranium to disposing of used fuel.

- Two Main Stages: It's broadly divided into the "front end" (preparing fuel) and the "back end" (managing used fuel).

- Uranium-235 is Key: Only a tiny fraction (about 0.7%) of natural uranium is the fissile isotope U-235, which we need to concentrate.

- Enrichment is Crucial: We boost U-235 levels to 3-5% to sustain the chain reaction in a reactor.

- Spent Fuel is Highly Radioactive: Used fuel requires careful handling, cooling, and long-term storage.

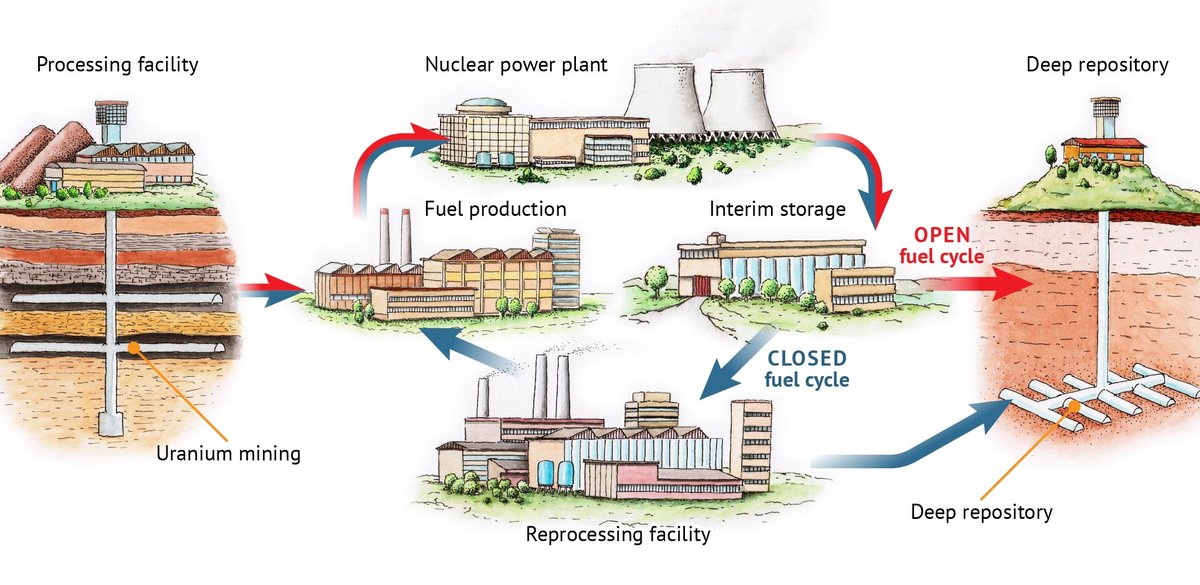

- Open vs. Closed Cycles: Nations choose different paths for spent fuel management – either disposing of it directly (open) or reprocessing it for reuse (closed).

- No Permanent U.S. Repository: The United States currently lacks a final underground disposal site for high-level nuclear waste.

The Front End: Fueling the Fission

The "front end" of the nuclear fuel cycle is all about preparation. It's the series of steps that takes raw uranium from deep within the earth and transforms it into the precisely engineered fuel assemblies ready to power a nuclear reactor. Think of it as refining crude oil into gasoline – a lot happens before it can run an engine.

1. Exploration and Mining: Hunting for Uranium

The first step in any fuel cycle begins with finding the source. Geologists are continually exploring the globe for new uranium deposits. Once identified, uranium ore is extracted through various mining methods, each chosen based on the deposit's characteristics.

- Underground Mining: For deep deposits, tunnels are dug, similar to coal mining, to extract the ore.

- Open Pit Mining: When deposits are closer to the surface, large open-air pits are dug, removing vast amounts of earth to access the ore body.

- In-Situ Leaching (ISL) or In-Situ Recovery (ISR): This method, common in the U.S., is a bit more subtle. It involves injecting a special solution (a lixiviant, typically oxygenated water with a bicarbonate solution) directly into the underground uranium deposit. This solution dissolves the uranium, which is then pumped to the surface for processing, leaving much of the surrounding rock undisturbed. It's often considered more environmentally friendly due to less surface disturbance and reduced waste rock generation.

Regardless of the method, the goal is the same: bring uranium ore to the surface so its energy potential can begin to be unlocked.

2. Milling and Refining: From Ore to Yellowcake

Once the raw uranium ore is extracted, it undergoes milling. This isn't just grinding it down; it's a chemical process designed to concentrate the uranium.

- Crushing and Grinding: The ore is first crushed and ground into a fine powder.

- Chemical Leaching: This powder is then mixed with chemical solutions (acids or alkalis) to dissolve the uranium, separating it from the unwanted rock and impurities.

- Precipitation and Drying: The dissolved uranium is then precipitated out of the solution and dried, resulting in a concentrated uranium compound.

The end product of milling is a bright yellow, powdery substance known as yellowcake (U3O8). This is a highly concentrated form of uranium, typically yielding about 1-4 pounds of U3O8 per ton of ore, meaning the raw ore itself contains only 0.05% to 0.20% uranium. Yellowcake is stable enough for safe transport and marks the first significant step in isolating the nuclear fuel.

3. Uranium Conversion: The Gaseous Transformation

Yellowcake (U3O8) isn't directly usable in most enrichment processes. For the next crucial step – enrichment – uranium needs to be in a gaseous form. This is where conversion comes in.

Yellowcake is chemically converted into uranium hexafluoride (UF6) gas, often simply called "hex." This process involves a series of chemical reactions, typically using fluorine. UF6 is ideal because it's a gas at relatively low temperatures, making it suitable for isotope separation technologies. It's also a solid at room temperature, which allows for easier storage and transport when not in gaseous form.

4. Uranium Enrichment: Boosting Fissile Power

Natural uranium contains two primary isotopes: uranium-238 (U-238) and uranium-235 (U-235). While U-238 makes up the vast majority (over 99.2%), it's U-235 that's the star of the show. U-235 is "fissile," meaning its nucleus can be split by absorbing a neutron, releasing immense energy and more neutrons, thus sustaining a nuclear chain reaction. However, natural uranium only contains about 0.7% U-235.

For most light-water reactors (the most common type worldwide), this natural concentration isn't enough to sustain an efficient chain reaction. So, we need to "enrich" it – increase the proportion of U-235. The goal is typically to boost the U-235 concentration to 3-5%.

Two primary methods dominate enrichment today:

- Gaseous Diffusion: This older technology involves forcing UF6 gas through a series of porous barriers. Because U-225 atoms are slightly lighter than U-238 atoms, they pass through the barriers a tiny bit faster. Repeating this process thousands of times in cascades gradually separates the isotopes, increasing the U-235 concentration. Gaseous diffusion plants are massive, consuming significant amounts of electricity.

- Gas Centrifuge: This is the more modern and energy-efficient method. UF6 gas is fed into rapidly spinning cylindrical rotors (centrifuges). The heavier U-238 isotopes are flung to the outer wall of the centrifuge due to centrifugal force, while the lighter U-235 isotopes concentrate nearer the center. The enriched gas is siphoned off, and the process is repeated in cascades. The sole operating enrichment plant in the U.S. uses gas centrifuges.

Advanced laser-based enrichment technologies, such as Atomic Vapor Laser Isotope Separation (AVLIS) and Molecular Laser Isotope Separation (MLIS), are also under development, promising even greater efficiency. The enrichment process is highly sensitive and controlled due to its potential dual-use nature (for both power and weapons).

5. Reconversion and Fuel Fabrication: Building the Core

With enriched UF6 gas in hand, it's time to turn it back into a solid form and shape it into fuel.

- Reconversion: The enriched UF6 gas is chemically reconverted into uranium dioxide (UO2) powder. Uranium dioxide is a stable, ceramic material well-suited for high-temperature reactor environments.

- Pellet Pressing: This UO2 powder is then compressed and sintered (heated at high temperatures) into small, cylindrical ceramic fuel pellets, each about 1 centimeter in diameter and height. These tiny pellets are the individual energy packets of the nuclear reactor.

- Fuel Rod Assembly: These pellets are then stacked and sealed into long, thin metal tubes, typically made of zirconium alloy, called fuel rods. The metal cladding acts as a protective barrier, preventing radioactive fission products from escaping into the coolant water and providing structural integrity.

- Fuel Assembly Bundling: Finally, multiple fuel rods (typically between 179 and 264 rods) are bundled together to form a fuel assembly. These robust assemblies are designed to withstand the harsh conditions inside the reactor core and allow for efficient heat transfer. A typical nuclear reactor core holds anywhere from 121 to 193 of these fuel assemblies, collectively containing millions of individual fuel pellets.

This meticulous fabrication ensures that the fuel is precisely engineered for safe and efficient operation within the reactor.

At the Reactor Core: Where the Magic Happens

With fuel assemblies ready, they are carefully loaded into the heart of the nuclear power plant: the reactor core. Here, the controlled nuclear fission of U-235 atoms generates immense heat, which is then used to produce steam, spin turbines, and ultimately generate electricity. This is where how nuclear power generators work truly comes to life.

Over time, as U-235 atoms fission, their concentration decreases, and fission products accumulate, "poisoning" the reaction. This reduces the fuel's efficiency. To maintain optimal power output, nuclear reactors operate on a refueling cycle. Approximately one-third of the reactor core (around 40-90 fuel assemblies) is typically replaced every 12 to 24 months. The removed assemblies, now known as spent nuclear fuel, are highly radioactive and require careful management.

The Back End: Managing Spent Fuel

The "back end" of the nuclear fuel cycle deals with the management of spent nuclear fuel, which is both extremely hot and highly radioactive. This stage is critical for safety and environmental protection, presenting some of the most significant challenges and public concerns associated with nuclear power.

1. Interim Storage: Cooling and Shielding

Immediately after removal from the reactor, spent fuel assemblies are intensely hot and emit high levels of radiation. They are first transferred to deep spent fuel pools located at the reactor site. These pools are filled with water, which serves two vital functions:

- Cooling: The water absorbs the residual heat generated by radioactive decay, preventing the fuel from overheating.

- Shielding: The water acts as an effective radiation shield, protecting personnel from harmful radiation.

Spent fuel typically remains in these pools for several years (usually 5 to 10 years) until its heat and radiation levels have significantly decreased. Once sufficiently cooled, the spent fuel may be transferred to dry cask storage containers, also located on-site. These massive, robust containers are typically made of steel and concrete, providing passive cooling (through air circulation) and multiple layers of shielding. Dry cask storage is a proven and safe method for long-term interim storage, designed to last for decades.

2. Final Disposal: The Long-Term Challenge

While interim storage solutions are robust, they are not permanent. The ultimate goal for spent nuclear fuel is final disposal in a secure, long-term repository. The ideal solution involves isolating this high-level nuclear waste (HLW) from the environment for hundreds of thousands of years, the time it takes for its radioactivity to decay to safe levels.

Currently, the most widely accepted scientific and engineering solution for final disposal is a geological disposal facility (GDF). This involves burying spent fuel deep underground in stable rock formations, thousands of feet below the surface. The layers of engineered barriers (the waste form itself, the container, backfill material) combined with natural geological barriers are designed to prevent radionuclides from reaching the surface environment.

However, developing and implementing such a facility is an enormous undertaking, fraught with technical, political, and social challenges. The U.S., for instance, currently has no operational permanent underground repository for high-level nuclear waste, despite decades of planning and significant investment in projects like Yucca Mountain. This lack of a final resting place means that all spent fuel in the U.S. continues to be stored in interim facilities at reactor sites or centralized storage facilities. This ongoing challenge highlights the complex interplay between science, policy, and public perception in the nuclear industry.

Two Paths: Open vs. Closed Fuel Cycles

When it comes to managing spent nuclear fuel, nations generally follow one of two broad strategies: the "open" (or once-through) fuel cycle or the "closed" (or reprocessing) fuel cycle. Each approach has its own set of advantages and disadvantages, influencing decisions about economics, waste management, and proliferation risk. This choice often depends on a country's energy policy, resource availability, and geopolitical considerations. You might find it interesting to consider how nuclear fusion differs from fission in its approach to fuel management, though its cycle is still conceptual.

1. The Open Nuclear Fuel Cycle (Linear)

In an open fuel cycle, once uranium fuel is mined, used in a reactor, and stored temporarily, it is then slated for permanent disposal without any further processing to extract usable materials. It's a linear, "use it once and dispose of it" approach.

- Advantages:

- Cheaper (Initially): It typically has lower upfront capital costs compared to building and operating reprocessing plants.

- Fewer Points of Failure/Risk: With fewer complex industrial processes, there are fewer opportunities for accidents or material loss.

- Smaller Radiation Doses (for workers): Workers in an open cycle generally receive lower cumulative radiation doses than those involved in reprocessing.

- Disadvantages:

- Generates Higher Volumes of High-Level Waste (HLW): All spent fuel, including unused uranium and plutonium, is considered waste, leading to a larger volume and mass that requires permanent disposal.

- Requires More Uranium Mining and Enrichment: Because no fuel is recycled, the demand for newly mined uranium and subsequent enrichment is higher.

- Resource Depletion: It doesn't make full use of the potential energy remaining in the spent fuel.

- Disposal Reliance: Heavily dependent on the successful development and implementation of a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF) for the entire volume of spent fuel.

2. The Closed Nuclear Fuel Cycle (Cyclical)

The closed fuel cycle takes a different approach. After spent fuel is used in a reactor and undergoes interim cooling, it is then reprocessed. Reprocessing separates the unused uranium and newly created plutonium (a fissile material) from the fission products. These recovered fissile materials can then be fabricated into new fuel for use in reactors, thereby "closing" the cycle.

- Advantages:

- Requires Less Uranium Mining and Enrichment: By reusing uranium and plutonium, the demand for virgin uranium ore and enrichment services is significantly reduced. This extends the life of uranium resources.

- Reduced Volumes of HLW: Reprocessing separates the highly radioactive fission products from the reusable materials. Only a small fraction (around 3%) of the spent fuel's mass is true high-level waste that needs permanent disposal, though this waste is more concentrated.

- Energy Security: Offers greater energy independence by reducing reliance on imported virgin uranium.

- Disadvantages:

- Expensive: Reprocessing plants are extremely complex, costly to build, operate, and maintain.

- Higher Radiation Dose (for workers): The reprocessing facilities are more complex and involve handling highly radioactive materials, potentially leading to higher occupational radiation doses.

- More Points of Failure/Risk: The increased number of processing steps introduces more opportunities for accidents, although modern plants are designed with stringent safety measures.

- Plutonium Proliferation Risk: Plutonium is a key component of nuclear weapons. Separating plutonium during reprocessing raises concerns about the potential for diversion of materials for illicit purposes, making international safeguards crucial.

The Global Picture: Fuel Cycle Choices Around the World

The choice between an open and closed fuel cycle is a significant policy decision with long-term implications. Different nations have adopted varying strategies based on their unique circumstances. This also plays into the broader advantages and disadvantages of nuclear energy from a geopolitical perspective.

- United States: The U.S. currently operates an open nuclear fuel cycle. Spent fuel reprocessing is not permitted, primarily due to concerns about the proliferation of plutonium for weapons purposes and the high cost of reprocessing. As noted, the U.S. also faces the challenge of lacking a permanent underground repository for its high-level nuclear waste, leading to all spent fuel being stored on-site at reactor facilities in spent fuel pools or dry casks.

- United Kingdom: The UK's approach has evolved over time. Currently, for its Advanced Gas-cooled Reactors (AGR) and Pressurised Water Reactors (PWR), the UK operates an open fuel cycle, with spent fuel stored at reactor sites or the Sellafield site. The UK has plans to develop a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF) for permanent HLW disposal. Historically, however, the UK did operate a closed fuel cycle. Its retired Magnox Reactors, for example, required reprocessing due to the vulnerability of their cladding to corrosion in wet storage. The Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (ThORP) at Sellafield also previously reprocessed AGR fuel until 2018. The shift towards an open cycle for AGRs was influenced by the relative affordability of mined uranium at the time and continued concerns regarding plutonium proliferation.

- Other Nations: Countries like France and Japan operate closed fuel cycles, seeing reprocessing as a way to enhance energy security, reduce waste volumes, and make more efficient use of uranium resources. Russia and China are also pursuing closed fuel cycle technologies.

These diverse approaches underscore the complexity and varying priorities in managing nuclear materials globally.

Common Questions & Misconceptions About the Nuclear Fuel Cycle

Nuclear power, and especially its fuel cycle, is often misunderstood. Let's address some common questions and clear up a few misconceptions.

Is nuclear waste really that dangerous?

Yes, spent nuclear fuel is highly radioactive and dangerous if not properly handled. It emits radiation that can be lethal with direct exposure. However, it's also important to understand that spent fuel is a solid material, not a liquid or gas that can easily spill or leak. It's meticulously contained, first in water pools, then in robust dry casks, and is slated for deep geological disposal to isolate it from the environment for millennia. The industry has an excellent safety record in managing this waste, and its volume is surprisingly small compared to other industrial wastes.

How long does spent fuel remain radioactive?

The radioactivity of spent fuel decays over time. Initially, it's intensely radioactive, with short-lived isotopes that decay rapidly. After about 10 years, its radioactivity drops significantly. However, some isotopes have half-lives of thousands to hundreds of thousands of years. For practical purposes, spent fuel is considered hazardous for hundreds of thousands of years, necessitating the long-term isolation provided by geological repositories.

Can we run out of uranium?

While uranium is a finite resource, current estimates suggest that known conventional uranium reserves, coupled with projected demand, are sufficient for many decades, possibly even centuries, with current reactor technology and open fuel cycles. If we consider unconventional resources (like uranium from seawater) and the widespread adoption of closed fuel cycles (which dramatically extend the energy yield from uranium), the supply becomes virtually inexhaustible for practical human timescales. Additionally, the future of nuclear energy could include advanced reactors that are even more efficient with uranium or thorium.

What about nuclear proliferation?

Nuclear proliferation, the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, is a serious concern, and the nuclear fuel cycle plays a role, especially at the enrichment and reprocessing stages. Both enriched uranium (above 20% U-235) and separated plutonium are materials that can be used to make nuclear weapons. This is why these stages of the fuel cycle are subject to stringent international safeguards and inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Countries choosing a closed fuel cycle must implement robust measures to prevent plutonium diversion. The goal is to ensure that nuclear technology is used exclusively for peaceful power generation.

Are there other types of nuclear fuels?

While uranium is the predominant fuel, research into other nuclear fuels exists. Thorium, for instance, is a fertile material (meaning it can be converted into a fissile isotope, U-233, in a reactor) and is more abundant than uranium. Thorium-based fuel cycles offer potential advantages in terms of waste characteristics and proliferation resistance, though they are not yet commercially deployed on a large scale.

The Road Ahead: Innovation and Sustainability

The nuclear fuel cycle is not static. It's an evolving ecosystem of technologies and practices constantly being refined to enhance safety, efficiency, and sustainability. Innovations are underway across the entire cycle:

- Advanced Mining Techniques: Developing more environmentally friendly and efficient ways to extract uranium.

- Enrichment Advances: Laser enrichment technologies could offer even greater energy efficiency.

- Advanced Fuels: Research into accident-tolerant fuels (ATFs) aims to improve reactor safety and performance, making fuel more resilient to extreme conditions.

- Next-Generation Reactors: The development of advanced reactor designs, including the promise of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), could change fuel requirements and potentially simplify waste management. Some advanced reactors are designed to operate more efficiently with spent fuel or even "burn" existing nuclear waste.

- Improved Reprocessing: New reprocessing technologies are being explored that aim to be more efficient, reduce proliferation risks, and minimize the volume and radiotoxicity of high-level waste.

The nuclear fuel cycle is a critical component in understanding the full scope of nuclear energy. It's a complex, multi-faceted process that, while presenting significant challenges, also offers immense potential for clean, reliable power generation. As global energy demands grow and the urgency to decarbonize intensifies, continued innovation and thoughtful policy in managing the nuclear fuel cycle will be paramount to realizing the full promise of nuclear power.