Types Of Nuclear Power Reactors And Their Designs: A Deep Dive into Nuclear Energy's Core

Step inside the heart of nuclear power, and you'll find a machine meticulously engineered to harness one of the universe's most powerful forces: nuclear fission. These incredible machines, known as Types of Nuclear Power Reactors, are the engines behind a significant portion of the world's clean electricity. They control atomic reactions to generate heat, turning water into steam that spins turbines and lights up our lives. But not all reactors are created equal; their designs vary dramatically, each with unique advantages, challenges, and roles in our energy future.

Understanding these different types isn't just for engineers; it's key to appreciating the innovation driving nuclear energy forward, from the established workhorses to the cutting-edge designs promising safer, more efficient power.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways

- Dominant Designs: Pressurized-Water Reactors (PWRs) and Boiling-Water Reactors (BWRs) are the most common reactor types globally, especially in the U.S.

- Safety First: Modern reactor designs prioritize passive safety systems, which rely on natural forces (like gravity or convection) rather than active controls, to prevent accidents.

- Fuel Flexibility: While enriched uranium is standard, some reactors can use natural uranium, thorium, or even create their own fuel.

- The Rise of Modularity: Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) are emerging as a game-changer, promising faster construction, lower costs, and increased deployment flexibility.

- Future Frontiers: Advanced designs like Molten Salt Reactors, Fast Breeder Reactors, and especially Fusion Reactors, are pushing the boundaries of what's possible in nuclear energy.

- Efficiency Drives Innovation: Reactors are constantly being refined to operate at higher temperatures and pressures, aiming for greater thermal efficiency and reduced waste.

The Heart of the Matter: How Nuclear Reactors Work

At its core, a nuclear reactor is an elaborate system designed to manage a controlled nuclear chain reaction. When the nucleus of a heavy atom, like uranium-235, is struck by a neutron, it splits in a process called fission, releasing energy and more neutrons. These new neutrons then strike other atoms, continuing the chain. A reactor's job is to ensure this reaction is steady and controlled, preventing it from spiraling out of control while capturing the immense heat generated.

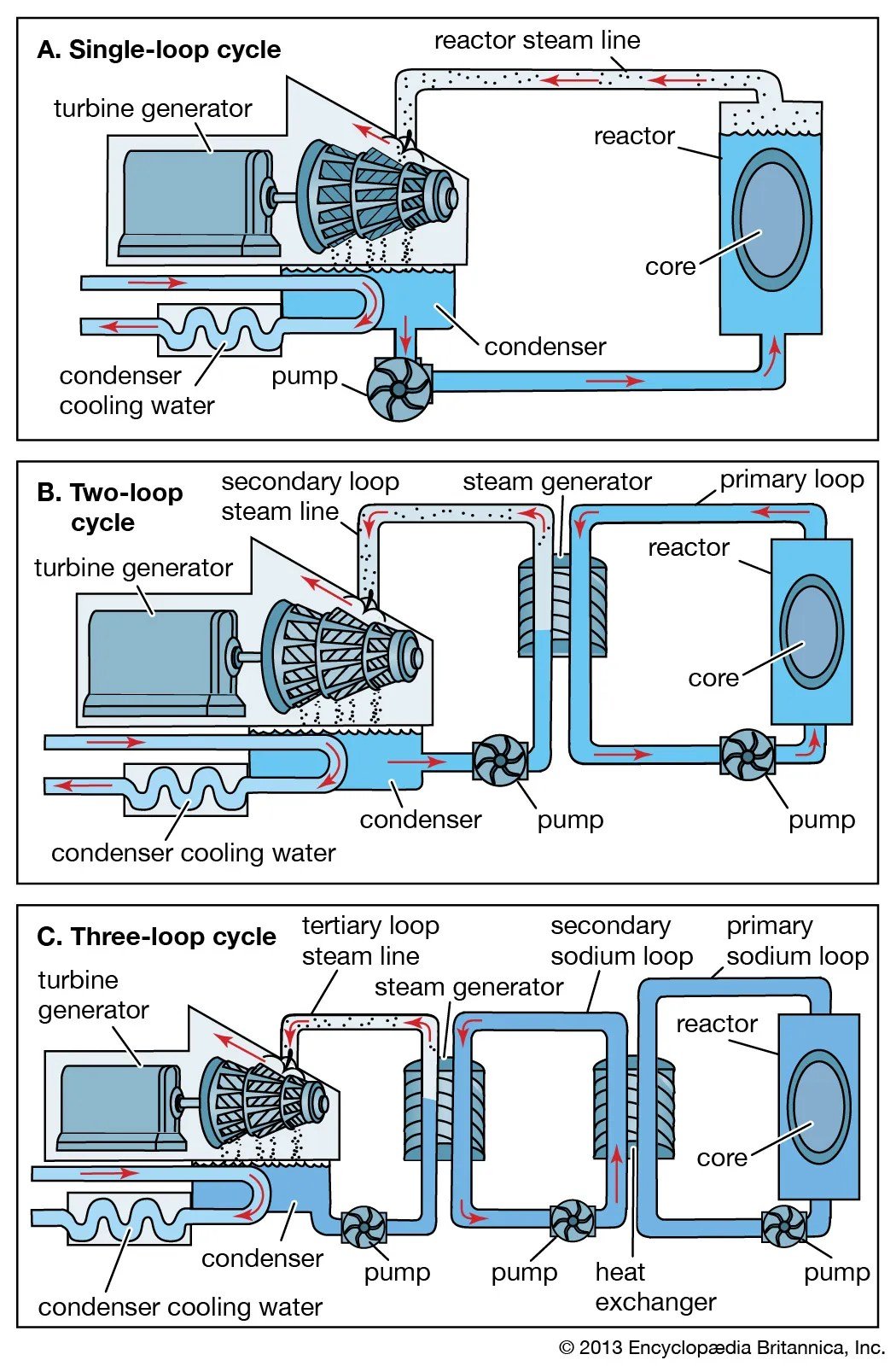

That heat is then transferred to a coolant—often water, but sometimes gas or liquid metal—which in turn creates steam. This steam drives a turbine, spinning a generator to produce electricity. It's a remarkably similar principle to how coal or natural gas plants work, but without burning fossil fuels and emitting greenhouse gases. To truly grasp the elegant mechanics, it helps to understand how a nuclear power generator works in concert with these reactor designs.

Now, let's explore the diverse engineering philosophies that bring this process to life.

The Workhorses of Today: Light Water Reactors

The vast majority of the world's operating nuclear power plants, particularly in the United States, employ light water reactors. "Light water" refers to ordinary water (H2O), used as both a coolant and a neutron moderator (slowing down neutrons to make them more likely to cause fission).

1. Pressurized-Water Reactors (PWRs)

Imagine a giant, super-hot pressure cooker that never boils. That's essentially a PWR. These reactors keep the water around the core under such high pressure that it remains liquid, even at temperatures exceeding 600°F (315°C). This superheated, radioactive water then flows through a separate heat exchanger—a "steam generator"—where it transfers its heat to a secondary loop of non-radioactive water, boiling that water into steam. This steam then drives the turbines. The primary (radioactive) loop never mixes with the secondary (clean) loop, a key safety feature.

- Advantages:

- Enhanced Safety: The two-loop design isolates the radioactive coolant, significantly reducing the risk of radioactive contamination in the turbine hall.

- Stability and Reliability: PWRs are known for their stable operation and robust design, making them ideal for large-scale, continuous power generation.

- Well-Proven Technology: With decades of operational experience, PWR technology is mature and highly standardized globally.

- Disadvantages:

- High Pressure Challenges: Operating at extremely high pressures necessitates robust, expensive construction materials and stringent safety protocols.

- Lower Thermal Efficiency: The heat exchange process involves a slight energy loss, leading to somewhat lower thermal efficiency compared to direct-cycle designs.

- Complex System: The need for separate primary and secondary cooling loops adds complexity to the overall plant design and operation.

2. Boiling-Water Reactors (BWRs)

BWRs simplify the process by allowing the water around the reactor core to boil directly. The reactor core heats the water, turning it into steam inside the reactor pressure vessel itself. This steam is then directly piped to the turbine to generate electricity. After passing through the turbine, the steam is condensed back into water and recycled to the reactor core.

- Advantages:

- Simpler Design: Eliminating the separate steam generator and secondary loop can lead to lower capital costs and a more compact plant footprint.

- Direct Cycle Efficiency: Direct steam generation within the reactor vessel can offer slightly higher thermal efficiency in some aspects by reducing heat transfer steps.

- Lower Operating Pressure: BWRs generally operate at lower pressures than PWRs, which can reduce some material stress.

- Disadvantages:

- Radioactive Steam: Since steam is generated directly in the reactor core, it carries trace amounts of radioactive isotopes, increasing the risk of contamination in the turbine and associated systems.

- Susceptibility to Thermal Shocks: BWRs can be more sensitive to rapid temperature changes, making reactor control more intricate during power fluctuations.

- Larger Containment: The need to contain the entire steam generation process within the reactor vessel often requires a larger containment structure.

Beyond Light Water: Alternative Coolants and Moderators

While light water reactors dominate, other reactor types explore different coolants and moderators to achieve distinct performance characteristics, often driven by fuel cycle considerations or safety enhancements.

3. Heavy Water Reactors (HWRs)

Heavy water reactors, most famously the CANDU (CANada Deuterium Uranium) design, use heavy water (D2O) instead of light water. Heavy water contains deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen with an extra neutron. This extra neutron makes heavy water an excellent neutron moderator, significantly more efficient at slowing down neutrons than light water.

- How it works: Heavy water circulates through the reactor core, acting as both coolant and moderator. Its superior moderating properties allow HWRs to operate efficiently with natural uranium fuel, which has a very low concentration of fissile uranium-235.

- Advantages:

- Natural Uranium Fuel: Eliminates the expensive and energy-intensive process of uranium enrichment, making nuclear fuel more accessible.

- High Neutron Economy: More efficient use of neutrons translates to better fuel utilization and potentially less spent fuel volume.

- Online Refueling: Many HWRs can be refueled while operating, avoiding costly shutdowns for fuel replacement.

- Disadvantages:

- Expensive Heavy Water: Producing and maintaining heavy water is costly, requiring specialized facilities.

- Complex Design: The core design, often involving hundreds of horizontal pressure tubes, can be more intricate than other types.

- Heavy Water Management: Leaks or loss of heavy water can be challenging to manage and can impact operational costs.

4. Gas-Cooled Reactors (GCRs)

Gas-cooled reactors use an inert gas, typically carbon dioxide or helium, as the primary coolant and graphite as the neutron moderator. These reactors were among the earliest designs and have evolved significantly.

- How it works: Fuel rods, often surrounded by graphite blocks, are cooled by hot gas circulating through the core. This superheated gas then transfers its energy to a heat exchanger, producing steam for the turbines.

- Advantages:

- High Thermal Efficiency: Operating at much higher temperatures than water-cooled reactors, GCRs can achieve greater thermal efficiency.

- Reduced Corrosion Risk: Gas coolants are non-corrosive and chemically stable, reducing wear on reactor components.

- Passive Safety Features: Some advanced designs feature inherent safety, as gas cannot boil away like water, and graphite has a high heat capacity.

- Disadvantages:

- Robust Materials: High operating temperatures and pressures demand advanced, heat-resistant construction materials, increasing costs.

- Large Core Size: Graphite's moderating properties can require a larger reactor core, which can complicate control systems.

- Coolant Leakage: While inert, managing high-pressure gas coolants and preventing leakage requires robust sealing technologies.

5. Advanced Gas-Cooled Reactors (AGRs)

An evolution of the earlier GCRs, Advanced Gas-Cooled Reactors are primarily used in the United Kingdom. They maintain the graphite moderator and carbon dioxide coolant but use enriched uranium oxide pellets in stainless steel cladding, allowing for higher operating temperatures and pressures.

- How it works: Similar to GCRs, CO2 gas circulates through the graphite-moderated core, heats up, and then passes through a heat exchanger to produce steam for the turbines. The design allows for higher power density and better steam conditions.

- Advantages:

- Very High Thermal Efficiency: Operating at even higher temperatures than traditional GCRs, AGRs achieve excellent thermal efficiency, maximizing electricity output from the fuel.

- No Water-Coolant Issues: The use of CO2 eliminates concerns about water reactions with the fuel or core components.

- Developed Technology: As a mature technology in the UK, AGRs have a proven operational record.

- Disadvantages:

- Complex High-Temperature Design: The need to operate at very high temperatures requires sophisticated materials and engineering, leading to higher construction costs.

- Limited Global Adoption: AGR technology is largely specific to the UK, limiting global supply chains and further development investment compared to more widespread designs.

- Graphite Aging: Long-term exposure to radiation causes graphite to change properties, which needs careful monitoring and management.

The Fuel Innovators: Reactors That Create More Than They Consume

Some reactor designs challenge the conventional notion of nuclear fuel consumption, aiming to extend our fuel resources or even create new ones.

6. Fast Breeder Reactors (FBRs)

Fast Breeder Reactors are designed to produce more fissile material than they consume. Instead of slowing down neutrons with a moderator, FBRs utilize "fast" (high-energy) neutrons. These fast neutrons can convert uranium-238 (a non-fissile isotope, abundant in natural uranium) into plutonium-239, which is fissile and can then be used as fuel.

- How it works: The core consists of a mixture of plutonium-239 and uranium-238. A liquid metal coolant, such as sodium or lead, is used because it doesn't slow down neutrons. This liquid metal transfers heat to a secondary loop, which then produces steam for the turbine.

- Advantages:

- Fuel Cycle Sustainability: FBRs can vastly extend nuclear fuel resources by utilizing uranium-238, which constitutes over 99% of natural uranium.

- Waste Reduction: Can potentially "burn" long-lived radioactive waste from conventional reactors, reducing the burden of waste disposal.

- High Efficiency: Extracts significantly more energy from uranium than conventional reactors.

- Disadvantages:

- Liquid Metal Challenges: Liquid sodium coolant is highly reactive with air and water, posing significant safety challenges and requiring specialized handling.

- Complex Design and Materials: The intricate design and specialized materials needed to manage fast neutrons and liquid metal coolants make FBRs expensive to build and operate.

- Proliferation Concerns: The production of plutonium-239 raises nuclear weapons proliferation concerns, requiring strict international safeguards.

7. Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs)

Molten Salt Reactors take a radically different approach: the nuclear fuel is dissolved directly into a molten salt, which then serves as both the fuel and the coolant. This liquid fuel circulates through the reactor core and a heat exchanger.

- How it works: A molten salt mixture, containing uranium or thorium, is heated by fission. This hot salt then transfers its heat to a secondary loop of non-radioactive salt, which then produces steam for power generation. The liquid nature allows for continuous refueling and removal of fission products.

- Advantages:

- Passive Safety: Operate at lower pressures than water-cooled reactors, reducing the risk of catastrophic vessel rupture. Many designs are "walk-away safe," meaning they can shut down and cool passively even without intervention.

- Continuous Refueling: Liquid fuel allows for easy, on-line refueling and chemical processing to remove fission products, enhancing efficiency and potentially reducing waste.

- Thorium Fuel Cycle: Well-suited for using thorium, a more abundant fuel, and can potentially "burn" existing nuclear waste.

- Disadvantages:

- Corrosive Salts: The molten salts are highly corrosive, requiring specialized, often expensive, materials for reactor components that can withstand these conditions.

- Technological Maturity: MSR technology is still in the developmental stage, requiring significant research and development to move from experimental to commercial scale.

- Regulatory Hurdles: Being a novel design, MSRs face a complex and lengthy regulatory approval process.

The Future is Modular: Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) aren't a new reactor type in terms of core physics, but rather a new paradigm for reactor deployment. They typically leverage existing, proven reactor technologies (often PWR or BWR designs) but scale them down significantly. The "modular" aspect means they are designed to be factory-fabricated as complete units or major components, then shipped to sites for assembly.

- How it works: SMRs operate on the same principles as their larger counterparts but are inherently smaller (typically under 300 MWe). Each module has its own containment and cooling systems, allowing for flexible scaling and decentralized power generation.

- Advantages:

- Reduced Construction Time and Cost: Factory production minimizes on-site construction, leading to faster deployment and potentially lower capital expenditure.

- Enhanced Safety: Smaller radioactive inventories and reliance on passive safety systems (like natural circulation for cooling) greatly increase safety margins.

- Flexible Deployment: SMRs can be sited in areas unsuitable for large plants, replace retiring fossil fuel plants, or provide power for remote communities and industrial sites.

- Scalability: Multiple modules can be added incrementally to match growing energy demand.

- Disadvantages:

- Economic Viability: While potentially cheaper per module, the overall economic competitiveness against large-scale reactors is still being proven.

- Regulatory Process: As a new deployment model, SMRs face new regulatory challenges and licensing pathways, which can be lengthy.

- Initial Investment: Despite eventual cost savings, the upfront R&D and certification costs for the first-of-a-kind SMRs are substantial.

Unlocking New Fuel Cycles: Thorium Reactors

Thorium reactors are another approach to nuclear power that seeks to leverage a more abundant fuel source than uranium. Thorium-232 is fertile, meaning it can absorb a neutron and transmute into fissile uranium-233, which can then sustain a chain reaction.

- How it works: Thorium-232 is placed in a reactor core. It absorbs neutrons, becoming protactinium-233, which then decays into uranium-233. This uranium-233 then fissions, releasing energy and more neutrons, some of which convert more thorium. Thorium reactors can be designed as molten salt reactors (MSRs) or solid-fuel reactors, and often require an initial "boost" from a fissile material like uranium-235 or plutonium-239 to kickstart the reaction.

- Advantages:

- Abundant Fuel Source: Thorium is roughly three to four times more abundant than uranium in the Earth's crust, offering a virtually limitless energy supply.

- Reduced Waste: Thorium fuel cycles produce significantly less long-lived radioactive waste compared to uranium cycles, and the waste generated is often less radiotoxic.

- Proliferation Resistance: Uranium-233 produced in a thorium reactor is usually co-mingled with uranium-232, which has properties that make it highly undesirable for weapons use, thus reducing proliferation risk.

- Disadvantages:

- Experimental Stage: Thorium reactor technology is largely experimental, requiring significant research, development, and demonstration before commercialization.

- Starting Material: Requires an external fissile neutron source to initiate the reaction, adding a layer of complexity.

- Infrastructure Shift: Transitioning to a thorium-based economy would necessitate substantial changes to the existing uranium-centric nuclear fuel cycle infrastructure.

Lessons from History: The RBMK Reactor

The RBMK (Reaktor Bolshoy Moshchnosti Kanalnyy – High-Power Channel-type Reactor) is a unique design, predominantly found in the former Soviet Union. It stands as a stark reminder of the critical importance of safety in nuclear engineering.

- How it works: The RBMK uses graphite as a moderator and light water as a coolant. The core consists of hundreds of pressure tubes, each containing uranium dioxide fuel assemblies. Water flows through these tubes, boiling into steam directly to drive turbines. A key feature is its ability for online refueling, allowing new fuel to be loaded without shutting down the reactor.

- Advantages:

- Online Refueling: Allows continuous operation without shutdowns for fuel replacement, maximizing electricity production.

- Natural Uranium Fuel: Can utilize natural (unenriched) uranium, simplifying fuel procurement.

- Disadvantages:

- Inherent Safety Flaws: Most notably, a positive void coefficient, meaning that if coolant water is lost, reactivity increases rather than decreases, leading to a dangerous power surge. This design flaw was a major contributor to the Chernobyl disaster.

- Complex Control: The channelized design and positive void coefficient made the reactor extremely challenging to control, especially at low power.

- Extensive Upgrades: Remaining RBMK reactors have undergone massive, costly safety upgrades to address these fundamental design flaws.

Inherently Safer Designs: Pebble Bed Reactors (PBRs)

Pebble Bed Reactors are a type of High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor (HTGR) known for their distinctive fuel form and passive safety features.

- How it works: The reactor core is filled with thousands of small, billiard-ball-sized graphite pebbles. Each pebble contains thousands of microscopic fuel particles (TRISO fuel). Helium gas flows through the bed of pebbles, absorbing heat. The hot helium can then directly drive a gas turbine or transfer heat to a secondary loop to produce steam.

- Advantages:

- Passive Safety: PBRs are designed with "walk-away" safety. If cooling is lost, the chain reaction naturally slows down as the core heats up (due to the Doppler effect and thermal expansion of graphite), and the pebbles can withstand very high temperatures without melting, preventing a meltdown.

- High Thermal Efficiency: High operating temperatures enable efficient electricity generation and can also be used for industrial process heat.

- Robust Fuel: TRISO fuel particles have multiple layers of protective coatings that act as miniature pressure vessels, containing fission products even at extreme temperatures.

- Disadvantages:

- Fuel Handling Complexity: Managing and processing the thousands of individual fuel pebbles, including their eventual disposal, can be complex.

- Limited Operational Experience: Few PBRs have been built or operated globally, making long-term viability and large-scale deployment uncertain.

- Power Density: The "loose" pebble bed design can result in lower power density compared to other reactor types.

Pushing the Boundaries: Advanced Designs on the Horizon

Innovation in nuclear power continues, with several advanced designs under development that promise even greater efficiency, safety, and sustainability.

12. Supercritical Water Reactors (SCWRs)

Supercritical Water Reactors are a "Generation IV" reactor concept that aims to combine the best features of light water reactors with the high thermal efficiency of supercritical steam cycles.

- How it works: SCWRs use water at a supercritical state, meaning it's neither a distinct liquid nor a gas, but a fluid with properties of both, capable of transferring heat very efficiently. This supercritical water acts as both the coolant and moderator, circulating through the core at extremely high pressures and temperatures (above the critical point of water: 22.1 MPa and 374 °C). The superheated supercritical water can then directly drive a turbine without needing a separate steam generator.

- Advantages:

- Ultra-High Thermal Efficiency: The supercritical state of water allows for significantly higher thermal efficiency (potentially up to 45-50%), leading to more electricity generation from the same amount of heat.

- Simplified Design: Eliminating the steam separator and dryer, and potentially the steam generator (for direct cycle designs), simplifies the plant layout.

- Smaller Footprint: High power density means a more compact reactor vessel and overall plant.

- Disadvantages:

- Extreme Operating Conditions: The very high pressures and temperatures demand advanced materials that can withstand these extreme conditions and resist corrosion, increasing costs.

- Developmental Stage: SCWR technology is still largely in the research and development phase, facing significant material science and engineering challenges.

- Water Chemistry: Maintaining precise water chemistry at supercritical conditions is crucial to prevent corrosion and deposition within the core.

The Ultimate Frontier: Fusion Reactors

While not fission reactors, fusion reactors represent the ultimate ambition of nuclear energy: harnessing the power source of the stars themselves. Instead of splitting atoms, fusion involves fusing light atomic nuclei (typically isotopes of hydrogen, deuterium and tritium) at incredibly high temperatures and pressures.

- How it works: Deuterium and tritium fuel are heated to extreme temperatures (millions of degrees Celsius) to form a plasma. This plasma is then confined, usually by powerful magnetic fields (in devices like tokamaks or stellarators) or by inertial confinement (using lasers), allowing the nuclei to fuse and release immense energy. This energy heats a working fluid, which then generates steam for a turbine.

- Advantages:

- Clean Energy: Produces no long-lived radioactive waste and no greenhouse gas emissions.

- Abundant Fuel: Deuterium is readily available from seawater, and tritium can be bred from lithium, offering a virtually limitless fuel supply.

- Inherent Safety: There's no risk of a runaway chain reaction; if confinement fails, the plasma simply cools, and the reaction stops.

- Disadvantages:

- Technical Challenge: Achieving sustained, controlled fusion that produces more energy than it consumes is one of the grand scientific and engineering challenges of our time.

- Extreme Conditions: The extreme temperatures and pressures require incredibly robust and complex materials and containment systems that are costly to develop and build.

- Experimental Stage: Fusion power is still very much in the experimental and research stage, with commercial deployment decades away.

Choosing the Right Reactor: A Complex Equation

As you can see, the world of nuclear reactors is incredibly diverse, reflecting a continuous quest for safer, more efficient, and more sustainable energy production. Each reactor type presents a unique balance of engineering complexity, operational advantages, fuel cycle considerations, and safety profiles.

The choice of reactor type for a new power plant isn't simple; it involves weighing economic factors, national energy needs, regulatory environments, and fuel availability. For established nations, proven PWR and BWR designs continue to be reliable options, while emerging technologies like SMRs are opening new possibilities for flexible, scalable, and safer deployments. Further down the road, advanced fission designs and ultimately fusion reactors hold the promise of transforming our energy landscape entirely.

The ongoing research, development, and thoughtful deployment of these different Types of Nuclear Power Reactors will play a critical role in shaping a future powered by clean, reliable, and abundant energy.